“It is plurality that defines us”: a Brazilian design guide

As part of our series exploring countries’ design cultures, we explore how Brazil’s politics of the past and present are affecting design, and how young designers are forging their own visual culture.

“To be a designer in Brazil nowadays is to be a survivalist,” says Fabiano Higashi, head of art at Wieden+Kennedy São Paulo.

A tough combination of poverty and gentrification, far right-wing leadership and cultural repression has made it so, he says. As a result, studios are struggling often, and designers are turning to tech companies and non-creative agencies for work.

It’s a hard set of circumstances in which to be creative, he admits, especially when the government’s harsh and prejudiced stances on women, the LGBTQ+ community, coronavirus pandemic and more “make Trump look like a good president”. Some parts of the industry are in “dire straits”. But while challenging, Higashi says it’s exactly this kind of environment that creative genius often comes from.

“Periods of repression are terrible, but at the same time they’re fertile ground for art and creativity – people look for ways to manifest themselves, protest, scream and appear,” he says.

“Those who want to work within barriers and those who want to break them”

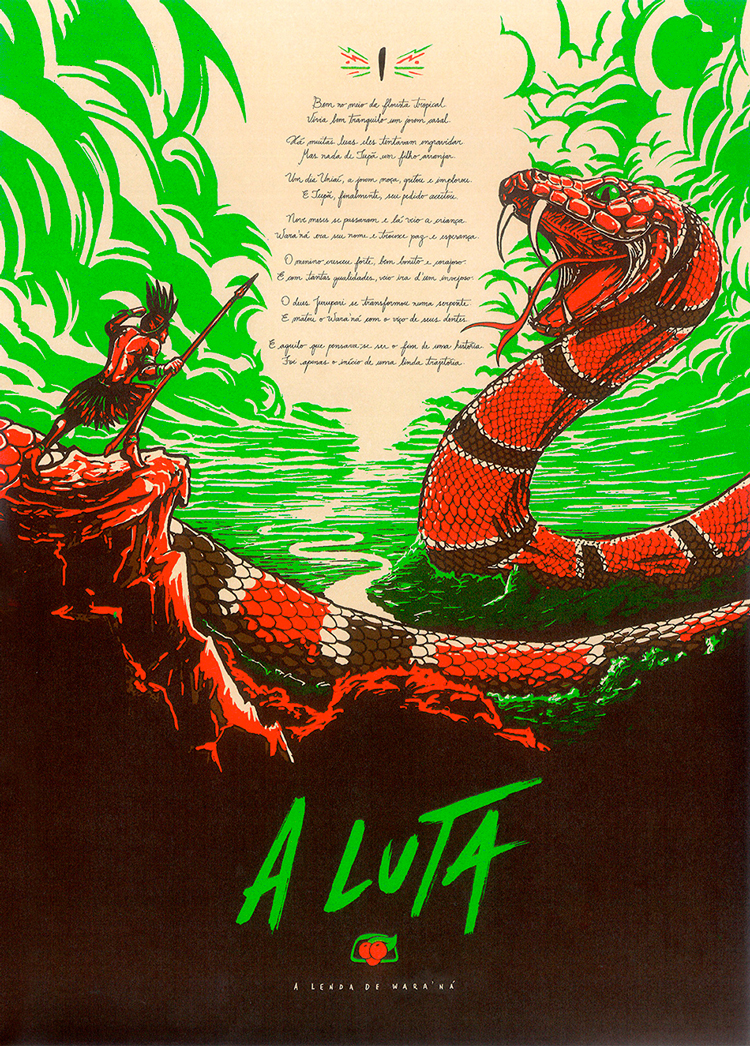

Despite a turbulent political history and more recent challenges, still Higashi is clear that creativity exists in Brazil in a big way. It’s right there on the streets, in fact. “If you look at where Brazilian visual art and design is today, part of it is happening on the streets – literally,” he says. “There’s a huge graffiti scene in cities like São Paulo and Belo Horizonte.”

This can be seen as a direct response to and rebellion against what Higashi calls the gentrification of art. He says it’s often the case that good art and design is shipped out to “galleries and foreign studios that are inaccessible to regular Brazilians”. On the streets, everyone can see everything.

Beyond those who take to the streets to share their creativity, Higashi says designers largely fall into two categories in Brazil: “Those who want to work within barriers and those who want to break them”. “The first group are seeking to organise the chaos we live in – they’re UX designers, design coaches, influencers, behaviourists, and fintechs and start-ups are desperate to hire these people,” he says.

“The other group is the rebel alliance – they’re unsatisfied and need to speak about their insecurities and sensibilities,” he continues. “Every work they do is a manifesto and an attempt at disruption and nowadays, I consider myself more a part of the second group.”

“University environments specifically dedicated to art and architecture”

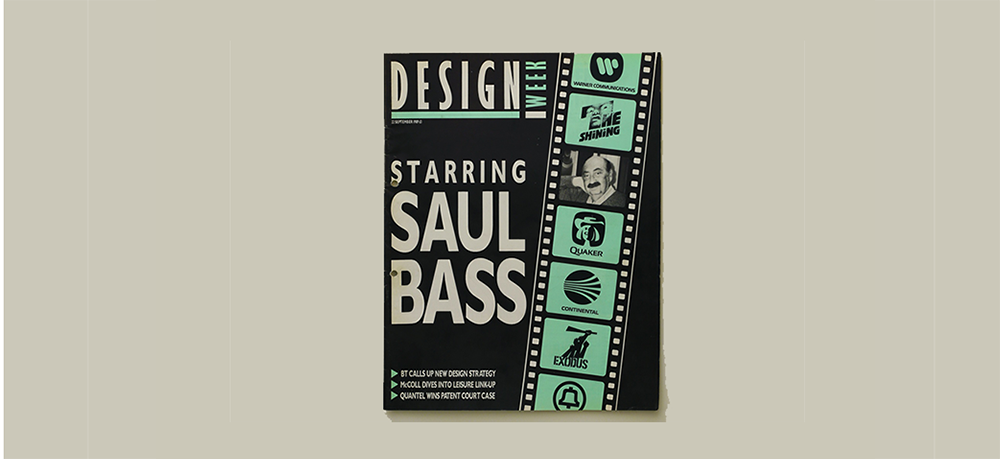

Brazil’s design industry hasn’t always been tested in the way it currently is, Higashi says. In the 20th century, he says there were many famous designers who contributed to the country’s “very solid” creative culture.

“We had the likes of Tarsila [a painter], Sergio Rodrigues [an architect], Rogério Duarte [an architect], Lina Bo Bardi [an Italian-born Brazillian architect] and Nieyemer [an architect], to name just a few we can be proud of,” he says. “We definitely see the work of these folk echoing in today’s Brazilian design.”

Architects make up a large part of Brazil’s design history because design as a singular educational discipline is a very new arrival in the country, according to Jaygo Bloom, BA Art and Design program director at Escola Britânica de Artes Criativas in São Paulo.

“The installation of the first undergraduate design courses in Brazil was a long process that started in 1962 with university environments specifically dedicated to art and architecture,” he says, adding that it was many decades later that most universities then split design disciplines into their own courses away from architecture and art.

Bloom explains that European institutions like the Bauhaus and the Ulm School of Design had a big influence on how architecture – and thus design – formed as an educational pathway. Ulm School of Design in particular had an effect, he says, since the country’s first architecture course at São Paulo State University (USP) modelled its curriculum on that created by Ulm co-founder Max Bill.

“It is vitally important our young designers recognise the history of marginality with their culture”

But while European design institutions were hugely influential in setting up the country’s design education system, such connection has its ramifications for the industry, Bloom says. “In the first half of the 20th century, the idea of projecting the image of a ‘modern day’ Brazil was the driving force behind all art, architecture, literature and design,” he says.

When European modernism reached Brazilian shores, many young creatives were “seduced into following this kind of aesthetic” because it felt so new, Bloom continues. Some of his students now, he says, question how they can bring cultural aspects of Brazil into their design work, without relying on stereotypes like carnival and football.

“It is vitally important our young designers recognise the history of marginality with their culture and question the use of the idealised images belonging to a culture wanting to be European, and examine what it is that makes Brazil so special, so different and unlike any other country,” says Bloom.

“Enhancing Brazilian identity with each piece”

As designers continue to embrace Brazil’s creative culture more than ever, Bloom says it’s an exciting period for the country in this respect. And this is a sentiment echoed by Ana Cristina Schneider, project coordinator for Sindicato das Indústrias do Mobiliário de Bento Gonçalves (Sindmóveis), an advocacy organization for the Brazil’s furniture designers and makers.

“In the last decade, Brazilian work has been distinguishing itself in the world precisely through the absorption of elements that are unique – from native wood species, to cultural elements such as northeastern lace and southern wool, and including cultural immersion in the creative process,” says Schneider. “It is precisely this plurality that defines us.”

As with so many other countries sustainability is one of the main drivers of the industry in Brazil, according to Schneider, and this again helps keep designers in touch with heritage craft and practices. The country is home to a plethora of natural materials, fibres and dyes and these are often paired with sustainably sourced secondary materials like recycled aluminium and reforested wood, she adds.

Artisanal handicrafts are incorporated into many pieces, Schneider continues, thereby “enhancing Brazilian identity with each piece”. And as Bloom adds, these pieces often contribute to the “flourishing” independent designers market scene.

“I can’t even imagine how fertile and revolutionary that is going to be”

When it comes to the fortunes of designers, it’s a mixed bag for Brazil. While Higashi, Bloom and Schneider all say there is hope to be found for the profession and its practitioners as they continue to forge their own creative culture, embrace old traditions and resist political pressure, there is no doubt it is a hard job.

That said, those Design Week spoke to were still positive about what is to come. “Both knowledge and technology are abundantly accessible and Gen Z and the so-called Alpha-Gen were born surrounded by creative tools that weren’t available to my generation,” says Higashi, who adds that the coming maturity of tech like AR and VR will provide even more opportunities. “I can’t even measure how fertile and revolutionary that going to be for everyone that loves design and creative possibilities.”

Looking to the future, Bloom ends: “It is vital that our current generation of designers learn to stand against injustice, and learn how to make a positive contribution to society and the economy. And it is as important that they come to understand what drives them and what injustices motivate them personally.”

-

Post a comment